Pacific Affairs has, over the years, celebrated and fostered a community of scholars and people active in the life of Asia and the Pacific.

It has published scholarly articles of contemporary significance on Asia and the Pacific since 1928. Its initial incarnation from 1926 to 1928 was as a newsletter for the Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR), but since May 1928, it has been published continuously as a quarterly under the same name.

The IPR was a collaborative organization established in 1925 by leaders from several YMCA branches in the Asia Pacific, to “study the conditions of the Pacific people with a view to the improvement of their mutual relations.” A precursor of contemporary “track-two” dialogue processes, the thirteen international conferences the IPR sponsored between 1925 and 1958 brought together scholars and policy leaders committed to developing a trans-Pacific community. The IPR was administered by the Pacific Council, which was composed of representatives from each of the autonomous National Councils of the member branches. The International Secretariat, the Pacific Council’s administrative organ, was located in Honolulu until it moved to New York in 1933.

While Pacific Affairs was published under the auspices of the entire IPR, the American Council produced a separate newsletter (Memorandum, 1932-1934). This became the journal Far Eastern Survey (1935-1961), published twenty-five times a year before 1953, and twelve times a year afterwards.

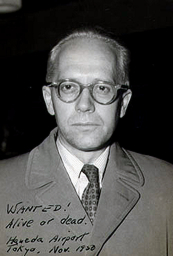

During the heyday of McCarthyism in America in the early 1950s, the IPR attracted fire as a hotbed of communism. McCarthy himself asserted that Owen Lattimore, a former editor of Pacific Affairs, was a “top Russian espionage agent in the United States.” After a year-long investigation, the United States Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws (the McCarran Subcommittee), claimed that “but for the machinations of the small group that controlled” the IPR, “China today would be free and a bulwark against the further advances of the Red hordes into the Far East.”

Although the charges were never substantiated, the resultant negative publicity damaged the IPR’s reputation, and exacerbated ideological divisions within the field of “Asian studies” in North America. The IPR also lost its tax-exempt status as an academic body in 1955 when the Internal Revenue Service alleged that the IPR had engaged in the dissemination of partisan (i.e. communist) political propaganda, had attempted to sway government officials towards such views, and had lobbied to influence government foreign policy. After a prolonged legal battle, the final judgment in 1959 found in favour of the IPR. However, despite the outcome, the depletion of resources from the various legal and political battles crippled the IPR, and it dissolved in 1960.

Remarkably, both Pacific Affairs and Far Eastern Survey continued to be published continuously through the various periods of turmoil. In 1961, the Far Eastern Survey became Asian Survey, with the editorial office relocating to Berkeley. As for Pacific Affairs, William L. Holland, who had been the editor since 1954 (Vol. 27), brought the journal with him when he moved to the University of British Columbia in Vancouver from New York in 1961.

Since its inaugural volume in its new home was published in 1961 (Vol. 34), Pacific Affairs has endured and thrived because it has served the important and necessary purpose of exploring the issues in Asia and the Pacific at a depth that goes beyond the usual headlines. The journal continues to be committed to informing scholars and policy makers about social, economic, and historical developments in a manner that combines specialized area knowledge with contemporary relevance.

Remarkably, both Pacific Affairs and Far Eastern Survey continued to be published continuously through the various periods of turmoil. In 1961, the Far Eastern Survey became Asian Survey, with the editorial office relocating to Berkeley. As for Pacific Affairs, William L. Holland, who had been the editor since 1954 (Vol. 27), brought the journal with him when he moved to the University of British Columbia in Vancouver from New York in 1961.

Since its inaugural volume in its new home was published in 1961 (Vol. 34), Pacific Affairs has endured and thrived because it has served the important and necessary purpose of exploring the issues in Asia and the Pacific at a depth that goes beyond the usual headlines. The journal continues to be committed to informing scholars and policy makers about social, economic, and historical developments in a manner that combines specialized area knowledge with contemporary relevance.

In the end, however, we owe our existence and our longevity to our contributors—not only the authors of our many articles, but the anonymous manuscript reviewers in the peer review process and the legion of scholars who have taken the time and effort to keep our considerable number of book reviews going. To all of you we extend our sincere appreciation and gratitude.

This community and our scholarly project have been sustained by a series of dedicated editors at Pacific Affairs, including Owen Lattimore, Elizabeth Green, Philip E. Lilienthal, Pete Chamberlain, R.S. Milne, Ian Slater and Tim Cheek, as well as a number of colleagues who took on shorter stints over the long history of the journal.

William Holland worked in the IPR from the 1920s, edited Pacific Affairs for one year in 1943 (Vol. 16) before returning to the helm in 1954 to guide the journal through the McCarthy period. He oversaw the move in 1961 to Canada and UBC. Over three decades, before he retired from the editorship in 1978, Bill made Pacific Affairs what it is today: the outlet of and resource for sustained scholarly research on contemporary Asian and Pacific issues. Generations of scholars recall their editorial contact with Bill and his endless encouragement to all scholars. It is fitting that the capstone event of each volume is the announcement of our William L. Holland Memorial Prize for the best article published in Pacific Affairs each year.

Hyung-Gu Lynn (Editor, 2008-2023)

Articles on the History of Pacific Affairs

A Word of Welcome

N. A. M. MacKenzie

Pacific Affairs, Vol. 34, Iss.1, 1961, pp. 4-6

William L. Holland and the IPR in Historical Perspective

John K. Fairbank

Pacific Affairs, Vol. 52, Iss.4, 1979

William L. Holland’s Contributions to Asian Studies in Canada and at the University of British Columbia

E. G. Pulleyblank

Pacific Affairs, Vol. 52, Iss.4, 1979, pp. 591-594

Source Materials on the Institute of Pacific Relations

William L. Holland

Pacific Affairs, Vol. 58, Iss.1, 1985, pp. 91-97

The Institute of Pacific Relations and the Origins of Asian and Pacific Studies

Paul F. Hooper

Pacific Affairs, Vol. 61, Iss.1, 1988, pp. 98-121

Editorial Items

Elizabeth Green (Editor)

Pacific Affairs, Vol. 1, Iss.1, 1928, pp. 16-17

First Article: “Two Wings of One Bird”

Dr. Hu Shih

Pacific Affairs, Vol. 1, Iss.1, 1928, pp. 1-8

First Book Review: “The Matrix of the Mind”

J. G. Condliffe

Pacific Affairs, Vol. 1, Iss.1, 1928, p. 27